Bill Seybold, Delaware Forest Service forest health specialist, performs an aerial survey of the state’s forest canopy in late-June for early detection of potential threats such as insect pests and diseases. This year’s survey revealed no major concerns.

DOVER – In late-June, Delaware’s forests get an annual “physical” or “check-up” – just after spring’s “leaf-out” blankets the state in a wave of green color. Just as people should visit the doctor to be screened for potential diseases, trees are examined with a variety of tools to hopefully spot minor issues before they turn into major ones.

Armed with a digital camera, GPS technology, and a tablet equipped with specialized software and satellite data, forest health specialist Bill Seybold boards a small plane for a sky-high view of the First State. The annual aerial survey is specifically designed to detect potential threats that can only be seen from the air.

For a total of 10 hours over three days in late-June, he carefully scans the forest canopy below him for areas of defoliation or discoloration: maybe oaks succumbing to a gypsy moth outbreak, or brown evergreens that could signal a potential southern pine beetle (SPB) infestation. A GPS tool linked to the tablet lets Seybold compare previous year’s maps to what he’s seeing now, as well as mark suspicious areas for further inspection and ground sampling.

Fortunately, early results from the 2018 aerial forest survey indicate no major outbreaks of tree diseases or insect pests. “No news is good news” could be an apt expression for forest health issues: 20 acres previously affected by SPB along the Delaware Bay has not grown in size. A three-acre outbreak of gypsy moth in Glasgow Park in New Castle County also seems to be contained. However, the aerial survey is just one tool the Delaware Forest Service uses to stay alert to what seems like an endless list of potential threats.

The agency currently monitors traps for walnut twig beetle (Pityophthorus juglandis), a vector for thousand cankers disease in black walnuts that was previously detected in Maryland. Forestry staff are also on the lookout for emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis) or EAB, a tree-killing insect that has destroyed millions of ashes across the United States, which was found in Delaware at a single purple panel trap in New Castle County in 2016. First discovered in the U.S. Michigan in 2002, EAB has now spread to 33 states. In addition to standard lure traps, staff also use a ground-nesting wasp (Cerceris fumipennis) found in baseball infields as a bio-surveillance tool to look for EAB nearby.

Other diseases include bacterial leaf scorch, an infection that primarily affects red oak species, and Asian long-horned beetle (Anoplophora glabripennis) or ALB, which primarily affects maple species, followed by elm and willow. Red maple is the most numerous tree in Delaware, so ALB could cause widespread damage if it was found in the First State. Newer threats are also emerging such as spotted lanternfly (Lycorma delicatula) or SLF, a tree pest found in Pennsylvania in 2014 that has been detected in nearby states, including Delaware in 2017. SLF poses a major threat to agricultural crops such as grapes, peaches, apples, and timber.

With the help of information and online resources, the public can play an important part in helping forest health professionals like Seybold do their work more effectively. For instance, people can learn how to identify spotted lanternfly at http://de.gov/hitchhikerbug and then use links on the site to report a possible sighting. By tracking and monitoring pests early, state officials might be able to mobilize a more rapid response.

The aerial survey is a key part of early detection, one tactic in a multi-pronged management strategy designed to keep forest threats – both native and non-native – at bay. For example, loblolly pine is one of the First State’s most commercially important trees, dominating the sandy Coastal Plain topography of Southern Delaware. Pine is most at risk for southern pine beetle (Dendroctonus frontalis), a native insect pest known as “one of the most destructive pests of southern pine forests.”

In a sign of potential shifts in long-term climate patterns, other Northeastern states have also gone on the alert against SPB. Rarely seen north of Delaware, SPB gained a foothold in the New Jersey Pinelands in 2010. And for the first time, New York’s Department of Environmental Conservation confirmed the presence of SPB in Long Island this year. Fortunately, Delaware has been vigilant in looking for early signs of an SPB outbreak and then cutting out the affected trees in a suitable perimeter to hold off movement to adjacent pines – an approach that has paid off so far.

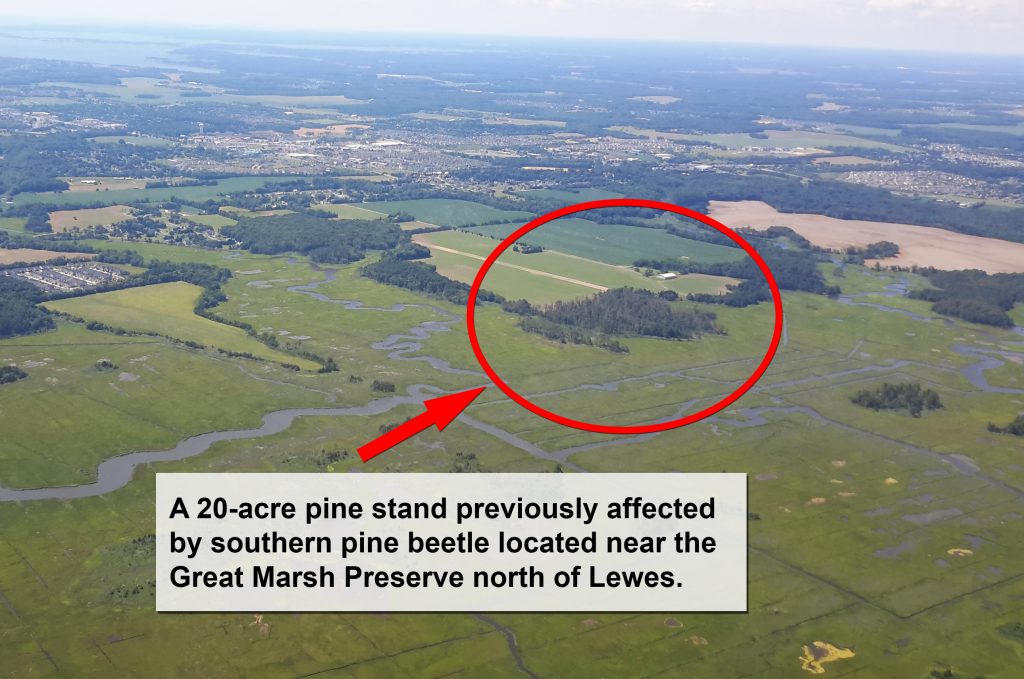

This aerial view of Delaware’s forests shows a previous infestation by southern pine beetle in the Great Marsh Preserve near Lewes.

Though SPB populations originally build up in stressed, overly dense, or damaged pine stands, once the population is at outbreak levels, it will move right through healthy pines. In the past several years, small areas of trees affected by SPB were found near Assawoman Bay and north of Lewes, possibly due to reduced tree vigor from salt water intrusion. Early detection and removal of infested trees can stop SPB populations from building up and moving through pine stands.

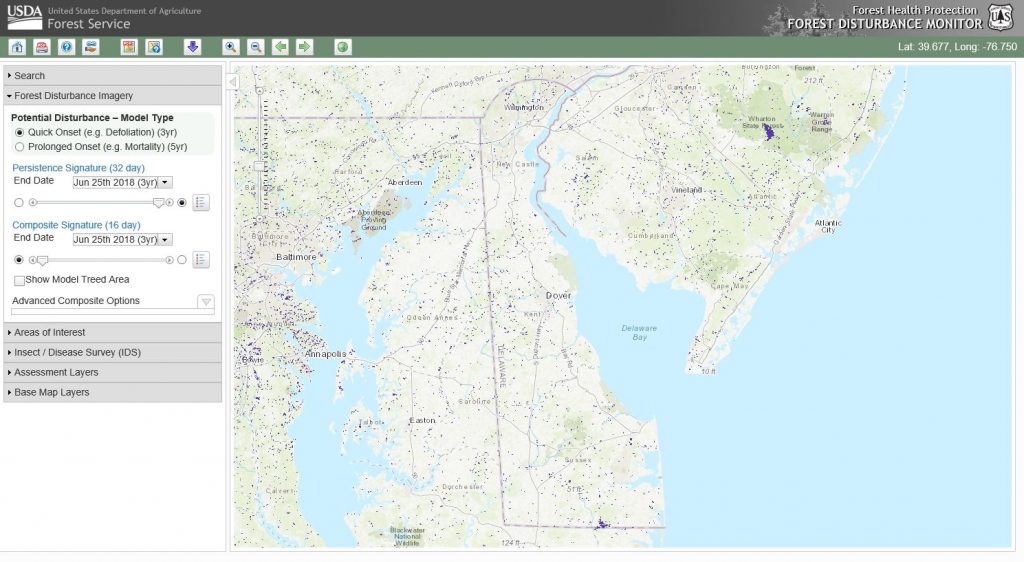

The U.S. Forest Service’s Forest Disturbance Monitor helps spotlight potential changes to forest canopy using satellite data.

The annual aerial survey is also linked with other tools such as the U.S. Forest Services Forest Disturbance Monitor (FDM), a sort of “smoke alarm” for potential forest health issues. It compares satellite data from several years and averages seasonal variation in green-up and forest loss to alert specialists such as Seybold to possible issues. Sometimes the “disturbance” might be due to commercial or residential land development, timber harvesting, or some other cause. The FDM is reviewed once every two weeks throughout the growing season, however, the aerial survey is usually done once per year in late-June, and is the only way to visually confirm the health of the state’s forest canopy.